This is the second part of an article written by Amy Madison, an investor, lawyer, and strategic advisor. You can find the first part of the article here. This piece, which focuses on Fundraising, Securities Laws, and Web3 Gaming originally appeared here and should not be taken as legal or investment advice.

“How can you design if you don’t know what the consequences of your decisions are? Creating something without any outcome in mind is not design but experimentation.”

— Virtual Economies: Design and Analysis

With high reward comes high risk. As the global gaming industry balloons to $336B in 2021, and web3 gaming exploding over 2,000% as the fastest-growing category, it’s easy for developers and investors who wish to enter this lucrative market to forget that timeless adage. Web3 gaming in particular comes with its own landmines, especially in the legal and regulatory department. I’ve developed this multi-chapter primer as your key to decoding the regulatory bodies that could dash your dreams of becoming (or funding) the next Sky Mavis or Web3 Epic Games. The name of the web3 development game: maximizing reward while minimizing risk.

The largest pain point for blockchain gaming is regulatory uncertainty. Not only do existing issues such as IP, consumer protection, and gambling applicable to traditional games remain in effect, but web3 games have additional challenges around convertible virtual currencies: NFTs, money transmission, and securities laws. Moreover, all of this is taking place against the background of still-nebulous regulations surrounding cryptocurrency in general. With the consequences of getting it wrong for developers ranging from fines to criminal charges, it is more important than ever to understand the legal landscape.

Games increasingly permeate all aspects of society, beyond entertainment, facilitating social engagements and financial transactions. As the industry continues its rapid evolution, I hope these chapters will inspire more conversations and critical analysis by bringing to light some of the challenges that investors and builders in this space should think about.

Nothing in this primer or the content associated with it should be interpreted as legal or investment advice. However I do encourage you to share this primer to educate your gaming development team and investors on the potential risks, and even consult with me for specialized advising.

What are Securities & Why Do They Matter?

Games are expensive to build. Gaming companies have traditionally raised money from publishers, crowdfunding platforms (e.g., Kickstarter, Indiegogo, or Gamefound), or by selling equity in the company to venture capitalists (VCs) and angel investors. With crypto, there are two additional ways to raise money now: by selling game tokens and/or NFTs. In this new paradigm, web3 gaming companies have been able to raise millions of dollars from both traditional investors, such as VCs, and a non-traditional class of participants - the public, via public token sales and NFT mints. However, while web3 games can open new avenues of fundraising, they may also put restrictions on others (e.g., crowdfunding platforms do not currently allow the sale of NFTs or crypto assets). They may also trigger securities law issues not traditionally considered by gaming companies when selling in-game currencies or virtual goods, leading some traditional institutional investors to shy away from making token investments due to the regulatory uncertainty.

“With crypto, there are two additional ways to raise money now: by selling game tokens and/or NFTs. However, while web3 games can open new avenues of fundraising, they may also put restrictions on others. They may also trigger securities law issues not traditionally considered by gaming companies when selling in-game currencies or virtual goods, leading some traditional institutional investors to shy away from making token investments due to the regulatory uncertainty.”

Securities refer to an enumerated list of financial instruments according to the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which include any note, stock, debenture, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement, and investment contract, amongst many others.

While many securities may be evident on their face (e.g., equities in a company), others are harder to categorize and may qualify as an “investment contract” (even if it doesn’t look like it on its face) based on the facts and circumstances (e.g., purchasing orange groves and the associated land tending services with expectation of significant profits). If you are deemed to be selling securities, such sale and subsequent interactions (e.g., transfer) are subject to a host of requirements and regulations under the Securities Act and the Securities Exchange Act and regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which may include limitations on who, where, and how much you can sell, and disclosures and reporting obligations.

The mission of the SEC is to protect investors from fraud and manipulation, and to promote the fair dealing and disclosure of important market information. Within the crypto industry, we’ve seen the SEC bring suits against issuers for offering unregistered securities without an exemption (e.g., Block.one, Kik Interactive Inc., Telegram Group Inc., Ripple Labs) to fraudulent initial coin offerings (many) to insider trading cases (ex-Coinbase product manager). We’ve even seen the SEC charge NVIDIA for inadequate disclosures in its financial reports for the impact that cryptomining has had on its gaming business, for which NVIDIA paid a $5.5MM penalty. In the latest news, the SEC charged Kim Kardashian for promoting a crypto project without disclosing the amount that she was paid, eventually settling for $1.26MM. All that said, we’ve yet to see formal rules or a clear framework on how to think about fungible and non-fungible tokens. As such, companies and founders are either leaving the US, or using best efforts to try to be compliant within the existing laws (which date back to 1933 or in the case of the Howey Test, 1946).

“We’ve even seen the SEC charge NVIDIA for inadequate disclosures in its financial reports for the impact that cryptomining has had on its gaming business, for which NVIDIA paid a $5.5MM penalty.”

If the asset that you’re selling is a security, then you may have to register with the SEC absent an exception or exemption. Similarly, if you’re facilitating the sale and exchange of a security, you may have to be registered as a broker dealer and register as an Alternative Trading System or national exchange, absent an exception or exemption. This means that tokens that are found to be securities would not be able to be traded on centralized exchanges such as Coinbase, FTX, or Binance in the US unless such exchanges were to obtain the required registrations. Theoretically, security tokens should not be traded on decentralized exchanges such as Uniswap, SushiSwap, or 1Inch either, but there are no central parties to hold accountable to obtain such registrations (due to the decentralized nature of the protocols). Profit sharing and crypto (whether fungible tokens or NFTs) are not allowed on the crowdfunding platforms, which limit the consideration from the company to goods, perks, and benefits.

“If the asset is found to be a security, the issuer will be subject to certain rules and regulations in how you sell the assets, including who you can sell to, where, how, and how much. This means that tokens that are found to be securities would not be able to be traded on centralized exchanges such as Coinbase, FTX, or Binance in the US unless such exchanges were to obtain the required registrations.”

If the asset is found to be a security, the issuer will be subject to certain rules and regulations in how you sell the assets, including who you can sell to, where, how, and how much. SEC Chairman Gary Gensler recently re-affirmed his predecessor, Jay Clayton’s infamous comment that, from their perspective, “most crypto tokens are investment contracts under the Howey Test.” This is relevant to the gaming industry, especially when dealing with tokens and digital assets such as NFTs, to determine whether the sales of the assets and the operations of your platform may be subject to securities laws.

“SEC Chairman, Gary Gensler recently re-affirmed his predecessor, Jay Clayton’s, infamously comment, that from their perspective, “most crypto tokens are investment contracts under the Howey Test.”

What is an Investment Contract & What is the Howey Test?

The Howey Test, named after the landmark 1946 Supreme Court case, is the predominant test that is used by courts to define an investment contract, a type of security. The Howey Test consists of four prongs, each of which must be satisfied for an instrument to qualify as a security: (1) An investment of money, (2) in a common enterprise, (3) with the expectation of profit, (4) from the efforts of others. If you’re a gaming company and are thinking of selling a game currency or asset (the issuer of the currency or asset, including any other affiliated promoters, sponsors, or third parties, collectively, the Active Participant or AP), run through this analysis to make sure you’re not inadvertently issuing an unregistered security.

“The Howey Test consists of four prongs, each of which must be satisfied for an instrument to qualify as a security: (1) An investment of money, (2) in a common enterprise, (3) with the expectation of profit, (4) from the efforts of others.”

In an attempt to mitigate US securities law concerns, common token structures will have an issuing entity (usually offshore) and a commercial operating entity that contracts with the issuing entity and performs various services (e.g., marketing, developing, maintenance, etc.). While these are separate entities, note that the SEC considers APs to include third-party affiliated entities, and there may be a risk that such entities are collapsed and viewed together as Active Participants. In other words, you shouldn’t assume that setting up separate corporate entities (even if they’re in different jurisdictions) may absolve you from regulatory scrutiny. The entity selling you the token may not be the entity that is responsible for launch and operation. We’ll go through each section of the Howey Test below in detail.

“You shouldn’t assume that setting up separate corporate entities (even if they’re in different jurisdictions) may absolve you from regulatory scrutiny.”

#1: An Investment of Money

If you’re selling a game currency, token, or asset for money or something of value to the purchaser, inclusive of goods or services, then this prong is usually satisfied. Even if you’re giving something away without cash consideration (in the case of an airdrop, whereby the issuer distributes tokens for free), this prong may inadvertently be triggered if you are receiving economic benefit from such distribution, e.g., marketing emails from the recipients or action of some sort in response to your promotional efforts.

#2: In a Common Enterprise

A common enterprise looks at whether the fortunes of the purchasers are linked together, usually with pro-rata distribution of profit (horizontal commonality), or to the success of the Active Participants (vertical commonality). There is currently a circuit split in which test courts apply to evaluate common enterprise, so we’ll look at both. The SEC has said that “when evaluating digital assets, we have found that a ‘common enterprise’ typically exists.”

Horizontal commonality requires the pooling of investor funds together in a common venture such that all investors share in the risks and benefits of the business. Given the non-fungible nature of NFTs, there is the argument that there is no pooling of investor funds at all, as each NFT is unique and should be treated as an asset on its own, one asset - one investor. For example, the fates of someone that purchases Punk 8376 and someone that purchases Punk 8377 are independent from another. The plaintiffs in the Dapper Labs (creators of NBA Top Shots) ongoing lawsuit present a counter argument. They argue that where the proceeds from the purchasers of the NBA Top Shot NFTs are pooled together by the company and used to conduct activities that increase demand (both in terms of attention and money) to the platform, and arguably the NFTs on such a platform, all purchasers benefit from the rising price. This is evidenced by the existence and rise of the “floor price,” the price of the lowest NFT within any given collection.

Vertical commonality exists when the fortunes of the individual investors increase or rise with the fortunes of the Active Participant. Most NFTs are structured so that the originator receives a secondary market royalty from the re-sale of the royalty. The higher the price of the NFTs, the higher the revenues received by the originator. These recurring revenue streams exist in perpetuity and often are multiples more lucrative than the original primary sale. Further, some games also run their own marketplaces, which charge transaction fees. In the case of Dapper Labs, which restricts the sale of NBA Top Shots to its own marketplace, they not only receive a resale royalty but also a transaction fee, any increase in the price of NBA Top Shots directly benefits the company. Where an Active Participant makes money based on the performance on the underlying asset, vertical commonality is likely to exist.

There is a variation of the vertical commonality test (dubbed “Broad Vertical Commonality”) that looks at the investor’s dependency on the Active Participant’s expertise. This test is usually the easiest to satisfy out of the three approaches, as it only focuses on the Active Participant’s expertise, which is usually greater than that of the investor’s.

#3: With The Expectation of Profit

When purchasers buy an asset with the expectation of making money, this prong is triggered. To evaluate this prong and the expectations of the purchasers, courts will look at how the asset is marketed, the features of the product, who is making the purchases, why, and for how much. For example, do the marketing materials emphasize returns and how much money can be made through the purchase? Do the assets come with profit sharing rights? Are the assets sold to expected consumers of the product, in amounts and at prices reasonably correlated to the expected consumption?

Absent any other factors (noted above), where price appreciation results solely from market forces, is not generally considered “profit” for the purposes of Howey. Further, this prong should be read in conjunction with the below, in that the profits should be derived from the efforts of someone else. If the purchaser is generating a profit from his or her own efforts from the utilization of the asset, then there is less of an argument that the asset is a security.

As part of this prong, courts will also look towards both the “consumptive purpose” of the tokens, and whether the purchasers are the appropriate audience that would be expected to consume such utility. In the Telegram case, where there may have been a use case for the GRAMS tokens (to store and transfer value across the Telegram network), the initial purchasers of the tokens were not potential users but rather financially sophisticated VCs purchasing the tokens at bulk.

Royalties, dividends, assets that generate income are typically features of investment instruments, and have greater chances of resembling a security. Revenue streams would trigger this prong, especially if promised at the fundraising stage, whereby purchasers would expect to generate streams of income from their investment (e.g., songs or IP that depend on the seller to secure licensing deals to generate revenues, which are then shared with the purchaser).

What happens if income generating activities and promises were made after the fundraising stage? That depends on who is making the promises and to whom.

“Royalties, dividends, assets that generate income are typically features of investment instruments, and have greater chances of resembling a security.”

“What happens if income generating activities and promises were made after the fundraising stage? That depends on who is making the promises and to whom.”

#4: From the Efforts of Others

Lastly, but certainly not least, the SEC and courts will look at how much the purchasers are depending on the Active Participants for the profits. In the context of digital assets, this is usually the prong with the most room to creatively structure. A simplified way to think about this prong is the more the sellers or developers do to increase the value of an asset, the more the asset will look like a security. This is why you often see mechanics requiring the purchaser to perform an action before the receipt of tokens, e.g., staking or other opt-in behavior that requires some effort on their part.

“This is why you often see mechanics requiring the purchaser to perform an action before the receipt of tokens, e.g., staking or other opt-in behavior that requires some effort on their part.”

“The more the sellers or developers do to increase the value of an asset, the more the asset will look like a security.”

In the context of gaming, where you sell an asset that can only be used in a game that you build, then the purchaser is reliant on you to build and maintain the game, including updating it and allowing the asset to have utility in game. If the asset can be moved off the game and utilized in other non-affiliated games or environments, then the purchaser is less dependent on you. The strongest case for lack of reliance is if the asset is still able to retain its value without an AP (e.g., Bitcoin), or even if the AP stops contributing and walks away (e.g., Vitalik or the Ethereum Enterprise Alliance, to the extent either would be considered an AP, could stop work, and the network would still exist). These situations are what SEC Director Hinman refers to as “sufficient decentralization.” Even if an asset is first sold as a security, it can be re-evaluated down the road, especially if “sufficient decentralization” is achieved, taking it out of securities classification. The SEC has yet to provide formal guidance on how to achieve this status or what characteristics it looks for in its determination.

“You may then ask, if an asset is sold as a non-security, can it thereafter become a security?”

You may then ask, if an asset is sold as a non-security, can it thereafter become a security? The answer, of course, is “it depends.” Technically, the Securities Act of 1933 regulates the offer and sale of securities. Each new offer and sale of an asset has the potential to turn an instrument into a security or investment contract, as it is the surrounding facts and circumstances of the event and not the instrument itself. We saw this in the case of Howey with orange groves, and Glen-Arden Commodities with casks of whiskey, where neither the orange groves or casks of whisky standing alone would be considered securities, absent the surrounding circumstances in each case. The Glen-Arden Commodities court, after citing Howey, noted that it is clear then that the manner in which the Scotch whisky warehouse receipts were sold, the information given, profits predicted, services promised and the obligations to be assumed by the purchasers were at all times relevant to the proceedings before the court.

Similarly, the purchase and sale of a token or NFT already in existence combined with facts and circumstances noted above, could turn that whole event into an investment contract, but wouldn’t taint the entire class of tokens or NFTs, unless it applied to them as a whole. Furthermore, such securities determination would only apply when all of the facts and circumstances are present, and wouldn’t apply to, for example, the original issuer of the token or NFT or any existing holders. In other words, the court in Howey found that the facts and circumstances under which he sold the orange groves constituted an investment contract, and not that all orange groves in existence became investment contracts following the case.

“The court in Howey found that the facts and circumstances under which he sold the orange groves constituted an investment contract, and not that all orange groves in existence became investment contracts following the case.”

“Even if an asset is first sold as a security, it can be re-evaluated down the road, especially if “sufficient decentralization” is achieved, taking it out of securities classification.”

The Reves Test

Lastly, if your asset resembles a note (debt instrument), you should run it through the Reves Test. This test assumes that the note is a security, unless it bears a "family resemblance" to one of the enumerated exceptions.

Securities Registration Exemptions

As a default, most companies have attempted to structure their offerings as non-securities. But given the lack of regulatory clarity regarding crypto, prudent companies should also structure any sales of their tokens within the guidelines of a securities offering exemption. Capital raising exemptions place requirements and restrictions on how many times a company can make an offering, how much they can raise, who they can market to and raise from, filing and disclosures, and resale and subsequent transfer.

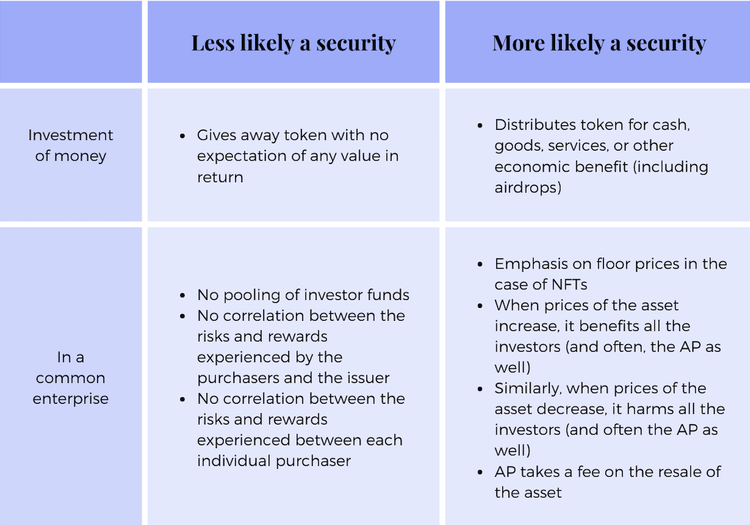

Recap — Howey Test Considerations

No single factor or prong is determinative of whether an asset is a security, however, the more items satisfied in the “more like a security” category, the more likely the asset will be one (i.e., if it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck …).

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) are member owned communities that are theoretically, autonomous and transparent, where smart contracts execute agreed upon decisions by DAO members. Within web3 gaming, we’ve seen developers, guilds, and investors and incubators form DAOs. Ideally, this means that ownership, control, and decision making is decentralized (widely dispersed and distributed) to many token holders that actively participate in the governance of the system through on-chain smart contract voting. True decentralization means that decisions are made by many, many token holders, which are capable of existing independently from an identifiable group of people, and thus, should reduce the risk of relying on the “efforts of others,” prong of the Howey Test.

In reality, however, most DAOs today operate as centralized organizations with a limited number of key decision makers that take in feedback from the community, which is represented by either voting on off-chain platforms like Discord or another chat app, or by using vote signaling platforms like Snapshot. A recent example of the slippery slope of the state of DAO voting today was with the Rari/Tribe drama. Earlier this year, Rari was hacked for approximately $80MM, and there was a vote on Snapshot whether to (1) make the affected users whole, (2) not make the users whole, or (3) propose an alternative. The community overwhelmingly voted (75%+) to make the affected users whole. Subsequently, Tribe DAO leadership held a second vote in June, which vetoed the initial proposal, and shortly thereafter, a third vote, asking the same question. In the last poll, the “community'', now buoyed by the votes of several delegates of the development company that deployed the Tribe DAO and their investors who previously had not participated in the first vote, strongly voted against making the affected users whole. This series of polls on the same question has led to criticism of leadership essentially disregarding previous polls and influencing voting until they get the results they want.

A recent example of the slippery slope of the state of DAO voting today was with the Rari/Tribe drama. Earlier this year, Rari was hacked for approximately $80MM, and there was a vote on Snapshot whether to (1) make the affected users whole, (2) not make the users whole, or (3) propose an alternative. The community overwhelmingly voted (75%+) to make the affected users whole. Subsequently, Tribe DAO leadership held a second vote in June, which vetoed the initial proposal, and shortly thereafter, a third vote, asking the same question. In the last poll, the “community'', now buoyed by the votes of several delegates of the development company that deployed the Tribe DAO and their investors who previously had not participated in the first vote, strongly voted against making the affected users whole. This series of polls on the same question has led to criticism of leadership essentially disregarding previous polls and influencing voting until they get the results they want.

“In reality, however, most DAOs today operate as centralized organizations with a limited number of key decision makers that take in feedback from the community, which is represented by either voting on off-chain platforms like Discord or another chat app, or by using vote signaling platforms like Snapshot.”

Further, even if votes were on-chain, most of the voting power is usually held by a small handful of centralized players (e.g., usually the early investors, VCs, and founding team) at least at the inception of any project. With reliance still on a group of recognizable players or Active Participants, these projects are neither decentralized, nor autonomous, and thus, likely still subject to securities law risk.

There are several other unanswered questions and related issues with regards to DAOs. Should DAOs incorporate formal corporate structures and if so, which jurisdiction should they incorporate in and under what structure? Who should do the incorporation? What type of liability, if any, do token holders have? How much power do DAOs have? We saw this question become particularly relevant in the Solend (a lending protocol on Solana) case, where the DAO initially voted to take over a whale account to prevent the flooding of a multi-million dollar liquidation on the platform in response to a margin call. This vote received massive backlash in the community and on Crypto Twitter, and was quickly reversed by a subsequent vote.

Implied Partnerships and Liability

At a most basic level, a partnership, in the formal legal sense, is formed when two or more people come together to do business. A partnership can be formal, if registered with the State and a partnership agreement is signed, or implied, based on actions. When creating or joining a DAO, it is important to determine whether an implied partnership may be formed.

For our purposes, there are two types of partnerships, general partnerships and limited partnerships. A general partnership is formed as soon as partners begin activities (most relevant in the case of implied partnerships). This usually means whenever DAOs start engaging in activities. General partners have unlimited liability. Limited partnerships require at least one general partner to take on unlimited liability, with passive limited partners only losing as much as they invested in the business.

Unlimited liability means a partner is personally liable for all business liabilities. If the partnership’s assets are not sufficient to satisfy such liabilities, the partner’s personal assets can get pulled in as well. Joint liability means that every person can be liable for the debt up to the full amount (can sue any partner). Several liability means that each party is only liable for their portion (can only sue the responsible partner). And joint and several liability is the same as joint liability, except that the partners can also then sue each other to collect their share. This is the default in a general partnership.

“Unincorporated DAOs could face the risk that they may be deemed implied general partnerships, with joint and several liability.”

“It is unclear whether the level of liability exposure correlates to the level of involvement or active participation on the part of the token holder or if all members are treated equally.”

Put together, this means that unincorporated DAOs could face the risk that they may be deemed implied general partnerships, with joint and several liability. It is unclear whether the level of liability exposure correlates to the level of involvement or active participation on the part of the token holder or if all members are treated equally. In a sense, the general partnership interest vs securities interests sit on opposite ends of a spectrum depending on the amount of control and participation the token holders have. In general partnerships where general partners have enough control and are not dependent on the efforts of others, such partnership interests are not deemed to be securities. Where the members (i.e., limited partners) are dependent on an identifiable party (i.e., general partners), the tokens or interests begin to look more like securities (especially triggering the reliance on the “efforts of others” prong), assuming all other prongs of the Howey analysis are met.

“DAOs are not immune from enforcement and may not violate the law with impunity.” In the CFTC’s view, the DAO is liable as a principal for each act, omission, or failure of the members, officers, employees, or agents acting for the Ooki DAO.”

In the latest series of cases by the Commodity and Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) against bZeroX, LLC, and its successor, Ooki DAO, the CFTC charged both for operating leveraged and margined retail commodity trading products without registration and failing to implement appropriate AML/KYC procedures in violation of the Bank Secrecy Act. The CFTC charged and settled with bZeroX, the centralized company and its founders, finding them personally liable as members of Ooki DAO. The Commission also served the DAO and all of its members in their help chat box on their website. The CFTC said that the attempt to transfer liability from a centralized entity to the community not only didn’t work, but served to extend exposure to the entire DAO. “DAOs are not immune from enforcement and may not violate the law with impunity.” In the CFTC’s view, the DAO is liable as a principal for each act, omission, or failure of the members, officers, employees, or agents acting for the Ooki DAO. It is unclear whether all members or only voting members are captured, and if so, for which votes and during which time frame(s). With the CFTC potentially poised to take over at the regulator of crypto spot markets, many will be watching this case for its impact on not only the future of DAOs, but the industry as a whole.

Aside from potential liability issues (which, as we’ve seen above, are not entirely foolproof), there are practical reasons for DAOs to have a corporate form. At some point, DAOs are likely going to need to interact with the real world, including hiring and paying contributors, interacting with vendors and service providers to open a bank account to transact in fiat, and paying taxes to the IRS. All of these acts generally require a legal entity to sign on behalf of the DAO. Note, in the absence of a legal entity, if you sign an agreement (even if on behalf of the DAO), you’ll be held personally responsible. Certain states, like Wyoming, have started to recognize DAOs, but such recognition does not extend nationally. Other legal scholars have also started to explore wrapping DAOs in legal structures, from traditional corporate forms such as the corporation or limited liability company to unincorporated non-profit associations to international structures. Choosing a legal wrapper and jurisdiction of incorporation of such legal wrapper will depend on the purpose of the DAO, its membership, and what it intends to do going forward.

It is important to note that even if a DAO does incorporate, if you then take actions on behalf of the corporate entity, there is a concept called “piercing the corporate veil,” in that you can still be held personally liable if the action was not really for the benefit of the corporation but rather to enrich yourself. In this case, courts will look through the corporate formality and hold the underlying individual responsible. One of the principles of partnerships is also that the members have their choice of partners. In widely distributed and fluid token memberships, where anyone can buy a token and join, this may possibly impact the decision. In comparison, this is likely not implicated in so-called DAOs where membership is permissioned, and the transferability of voting tokens restricted. All of this and more, may be impacted by the results of the closely watched Ooki DAO matter, in which, the CFTC, if left unchallenged, may have its way in finding that all members of the DAO are liable.

Web3 Gaming Guilds

Guilds, while not a new concept in gaming, have arisen as an interesting and novel way to participate in web3 games. As noted above, the initial iteration of web3 games relied heavily on NFTs, especially as a gating function to gameplay. In order to play the game and earn tokens, players had to purchase or otherwise obtain one or more NFTs. During the height of the bull market, some of these NFTs rose to several hundred and even several thousand dollars. This became unaffordable and inaccessible for many players, most of whom were located in developing countries such as the Philippines and Venezuela.

Yield Guild Games (YGG) was one of the first gaming guilds to come into the spotlight. Originally, it was created to allow players to rent Axies in order to play the game. The renters of such Axies, dubbed “scholars”, would be able to use YGG’s Axies to play the game, earn SLP, and in exchange, would share a percentage of their earnings with the guild (in the case of YGG, the Guild receives 10% of the revenue, a manager receives 20%, and the player keeps the remaining 70%). Since then, other guilds have formed, which focus on different geographies (local guilds), types of games, revenue sharing models, value-add services such as scholar training programs, or game revenue maximization strategies (e.g., Blackpool, which DIGITAL is an investor in, uses metrics and bespoke quantitative strategies to maximize yield for its members).

DAOs can also have sub-DAOs (similar to subsidiaries in the traditional corporate sense), where the parent DAO can have part or whole ownership in a sub-DAO. In the case of YGG, we’ve seen several sub-DAOs in local geographies, whereby YGG will make investments in the tokens of the sub-DAO.

Gaming guilds like YGG are generally structured as DAOs, and are collectives of players that come together for a shared purpose. YGG’s website states: “we bring players together to earn real money from playing NFT games like Axie Infinity, The Sandbox, League of Kingdom and other blockchain based game economies. As members of Yield’s Guild’s Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO), we collectively vote to decide what games we want to play, what virtual assets we invest in, and how we will use them in-game.” Most guilds are structured in a similar way, with the guild partnering with games, often making investments via tokens and/or NFTs, and building up a "fund" or pool of assets that are collectively owned by the token holders. There are questions as to how and when to thereafter distribute the assets, who actually makes the investment and distribution decisions, and whether or not this starts to look like investment management activity.

Almost all guilds have a token, and as such, should consider the Howey Test mentioned above. The tokens are usually purchased for money. There is usually common enterprise, horizontal where the holders of the tokens share the same risks and benefits, and vertical where the risks and benefits of the token holders correlate to that of the founders and Active Participants of the guild. There may be an expectation of profit depending on the marketing and communications and whether token holders are purchasing the tokens with the expectation that the token price will rise or that they will receive revenue sharing benefits (the latter may trigger the enumerated security, participation in a profit-sharing scheme by itself).

Lastly, are the purchasers relying on the Active Participants to make such a profit? In instances where the guild founders emphasize their particular expertise, that may be evidence of greater reliance on the Active Participants. That said, where token holders/guild members are actively taking actions to contribute to their fortune, in most cases gameplay and the supplying of game assets to the DAO, then there may be less of an argument of a dependence on the efforts of others. That said, courts will also look towards how much active management there is of what is otherwise an investment portfolio of fungible tokens and NFTs by the guild, and how much of a role the average token holder will play in that determination.

Lastly, guilds, just like any other organization, can face legal troubles. We’ve seen one of the first guild-to-guild come up recently, with the YGG-Merit Circle legal battle. Merit Circle is a gaming guild with a similar mission as YGG. YGG had made an investment of $175,000 via a simple agreement for future tokens (SAFT) into Merit Circle, in exchange for the future delivery of MC tokens. Earlier this year, Merit Circle put up an improvement proposal to its DAO, proposing for the termination of the SAFT and the refund of the initial investment for YGG’s “lack of value” to the DAO. By then, the value of the MC tokens had already gone up several fold from YGG’s initial investment.

There are a few issues in this instance, and most have to do with contract law rather than the novelty of the parties at play. First, in a standard SAFT, there are no relevant termination provisions that would allow Merit Circle to terminate the agreement without breaching the agreement. Second, there was no provision in the SAFT that required YGG to “provide value” to Merit Circle as part of the consideration for the investment. And lastly, at the time of the controversy, the MC tokens had already appreciated materially, and if a fair refund was to be made, it arguably should have been on fair market terms, and not the purchase price. The parties eventually settled the matter for $1.75MM, agreeing to terminate the agreement and issued a joint press release on the matter.

This case is interesting because, had the matter gone to court, and say Merit Circle was found to be in breach of contract, then who from Merit Circle would be liable at the end of the day? For the sake of the hypothetical, say there were damages, and the Merit Circle treasury didn’t have enough funds to cover the damages. Would it be the guild founders? The people that voted on the proposal to terminate the agreement? All MC token holders? This case highlights the importance of setting clear expectations up front and possibly inserting additional language into the purchase agreements, where there may be a need for future recissions, or terminations based on milestones reached by either party.

Tokenomics & Design Considerations

Fungible Tokens

Today, web3 game tokenomics are structured as single- or dual-token models (we’ve even started to see three-token models!). In single-token models, there is one token that is used for governance and in-game consumption. More commonly, we’ve seen games adopt dual-token models, where the tokens are split into governance tokens (e.g., Axie’s AXS, Star Atlas’ POLIS, Stepn’s GMT) and in-game utility tokens (e.g., Axie’s SLP, Star Atlas’ ATLAS, Stepn’s GST). Governance tokens, typically issued by a DAO, are intended to control the development and operations of a game, including the DAO treasury. They are usually fixed in supply. Utility tokens or in-game currencies, on the other hand, are intended to be the means of exchange within a game and are given as rewards for completing tasks and used for microtransactions, such as buying and selling game assets, such as NFTs. They are usually open ended in supply and are subject to inflation risk. These functions are arbitrary and subject to the creative design by the developers, and sometimes we’ve seen governance tokens can also be used for in-game transactions, such as when Axie introduced AXS costs for breeding Axies.

“Utility tokens or in-game currencies, on the other hand, are intended to be the means of exchange within a game and are given as rewards for completing tasks and used for microtransactions, such as buying and selling game assets, such as NFTs. They are usually open ended in supply and are subject to inflation risk.”

Before deciding on how many tokens to issue, you should think about what purpose each token will serve and how the value of the company will be divided between the tokens. Fundraising and speculation are commonly, but should not be the primary drivers of creating a token, as that will not only trigger securities law implications, but also create unsustainable economies and misalign with player expectations. What other reasons are there for having two tokens, and are the purchasers the actual consumers of the proposed utility of such tokens? While both are tokens, often with the same Active Participants, they may receive different securities treatments based on their surrounding facts and circumstances, and thus, it is recommended to evaluate each one individually.

“Before deciding on how many tokens to issue, you should think about what purpose each token will serve and how the value of the company will be divided between the tokens. Fundraising and speculation are commonly, but should not be the primary drivers of creating a token, as that will not only trigger securities law implications, but also create unsustainable economies and misalign with player expectations.”

For example, with regards to the first prong of Howey, governance tokens are typically sold, while game currencies are usually earned by staking governance tokens, completing quests or winning battles. Similarly, governance tokens are more likely to be held by investors that participated in a token pre-sale, whereas in-game currencies are likely to be held by players of the game and consumed in-game. With this context, you need to be especially careful about the sale, design, and issuance of governance tokens, as to not inadvertently trigger securities law implications.

Governance tokens, in theory, should allow token holders to make game design and development decisions regarding game direction, character and story creation, and game economics, as well as take control of the game treasury. That said, most of these decisions are heavily dependent on centralized players, and arguably should be, given that game design is incredibly difficult, specialized, and should probably not be crowd-sourced. Most projects today acknowledge this and have built in a period of centralization, usually a few years, corresponding to lock-up periods, where the initial team retains control of game design and development.

“Governance tokens, in theory, should allow token holders to make game design and development decisions regarding game direction, character and story creation, and game economics, as well as take control of the game treasury.”

Given that these tokens are traded on public secondary markets, speculation will happen, and it is better to isolate the speculation and potential price fluctuations to one token. As more people enter the game economy, it should drive up the demand of the in-game currency. By providing mechanics to increase the supply of the in-game currency, and also sinks to decrease the supply when needed, you can pull levers to keep the currency stable.

The latest wave of web3 games has seen tokens being sold in pre-sales ahead of the game being built (which can be a several-year endeavor), or simultaneous to parts of the game being developed. With popular, anticipated games, speculators rush in and push up the price of the tokens (e.g., Illuvium’s ILV or Star Atlas’ POLIS token). Token holders generally have lock-ups, and/or are incentivized to hold onto their tokens via staking mechanisms, whereby they could voluntarily lock their tokens in exchange for additional governance tokens or more commonly, in-game currency tokens. Once the lock-ups expire, this has the potential to cause a mass exodus of token holders (generally motivated by financial reward, and not gameplay), as they sell the tokens, causing the token price to fall.

“Once the lock-ups expire, this has the potential to cause a mass exodus of token holders (generally motivated by financial reward, and not gameplay), as they sell the tokens, causing the token price to fall.”

Web3 in-game currencies differ from traditional in-game currencies in a major way, in that they are usually traded on liquid secondary exchanges and thus have a floating value. Unlike V-bucks, which usually have a fixed price of 1,000 V-bucks for $10 (or, $8, if you purchase directly from the Epic store), the prices of tokens like SLP are subject to fluctuating supply and demand pressures both within and outside of the game. For a healthy and sustainable game, it is preferential for an in-game currency to stay relatively stable and predictable. In Axie, where SLP is earned by completing tasks and burned by breeding new Axies, an imbalance (amongst other factors) caused SLP supply to inflate, and prices to plummet. To combat this, the Sky Mavis team (creators of Axie) had to step in to tweak some gameplay mechanics to make it more difficult to earn SLP. The more a centralized party (efforts of others) needs to step in to manage the monetary policy of an asset, the more likely the last prong of Howey will be triggered.

Non-Fungible Tokens

Similarly, there are a few flavors of NFTs that are usually sold in a game. Game play pieces or characters such as avatars representing your identity, cosmetics such as accessories or skins, and land on which you can usually build. Sometimes these can also operate as access passes to the gameplay themselves. Similar to the CVC analysis covered in Chapter I of this series, the more fungible characteristics one adds to an NFT, the more likely it may trigger securities analysis. While the unique nature of NFTs should take them out of securities law purview (mostly due to the common enterprise prong noted above), fractionalizing an NFT into many pieces or creating hundreds or thousands of cosmetic assets that are indistinguishable from one another (e.g., ERC 1155 standard cosmetic assets) may cause issues if all of the other prongs of Howey are satisfied.

“While the unique nature of NFTs should take them out of securities law purview (mostly due to the common enterprise prong noted above), fractionalizing an NFT into many pieces or creating hundreds or thousands of cosmetic assets that are indistinguishable from one another may cause issues if all of the other prongs of Howey are satisfied.”

When web3 games first started taking off, NFTs were required to play the game. For example, to play Axie Infinity, users need to acquire three Axies, which will set them back a few hundred dollars. To play Stepn, the popular walk-to-earn game, a pair of NFT shoes will cost a similar amount, with a more expensive shoe unlocking more rewards. As such, they served as game passes in the traditional sense, providing access to content. Recognizing this gating friction as a perverse incentive to gameplay, the industry has since started to pivot towards a free-to-play model, where NFTs are optional and incremental to gameplay, but not required. Axie has since launched Origins, which allows users to play the game without the purchase of any NFTs. Most recently, Limit Break pioneered another version of free-to-play, dubbed free-to-own, in which Digidaigaku NFTs were released to the public through a free mint. These NFTs give holders access to airdrops and will be used later down the road in a MMO game.

“The initial iteration of web3 gaming has seen an unhealthy expectation of profit from every asset and game currency.”

The initial iteration of web3 gaming has seen an unhealthy expectation of profit from every asset and game currency. This has not only been evidenced by market trading and speculation of game currencies (especially governance tokens), and assets (for the purpose of investment, and not gameplay), but also by people (especially in the Philippines and Venezuela) quitting their day jobs with the expectation that they’ll continue earning the same level of income, if not more, from gameplay. Increases the cost of entry for new players where NFTs are required for play, and is unsustainable, as where is the money coming from. Price depressions have led to an exodus of interest from both new and existing players.

Traditional publishers have taken different approaches to blockchain and NFTs: Ubisoft experimenting with it, Mojang (Minecraft) ban them from game, and Epic saying that it will not incorporate into their own games, but open to having them in the Epic Store (Gala Games and Blankos Block Party), as long as they abide by regulatory reporting and tax laws. On the topic of blockchain gaming, Tim Sweeney said: "As a technology, the blockchain is just a distributed transactional database with a decentralized business model that incentivizes investment in hardware to expand the database's capacity. This has utility whether or not a particular use of it succeeds or fails … Developers should be free to decide how to build their games, and you are free to decide whether to play them. I believe stores and operating system makers shouldn’t interfere by forcing their views onto others. We definitely won’t." Steam, the largest store for PC games, has banned blockchain games.

“On the topic of blockchain gaming, Tim Sweeney said: “As a technology, the blockchain is just a distributed transactional database with a decentralized business model that incentivizes investment in hardware to expand the database’s capacity. This has utility whether or not a particular use of it succeeds or fails … Developers should be free to decide how to build their games, and you are free to decide whether to play them. I believe stores and operating system makers shouldn’t interfere by forcing their views onto others. We definitely won’t.”

To manage expectations and create sustainable and challenging gameplay environments, and take advantage of the programmable nature of blockchains, consider adding decaying features to NFTs, where it makes sense. In Diablo II, the characters reset with each new season. In Escape from Tarkov, the game developers Battlestate Games reset the game (i.e., clear all progress, skills, inventories, missions, and player stats), or “wipe” the game every six months, corresponding with major updates. These features would also likely reduce the expectation of profit on part of the player and purchaser.

Other Considerations

SAFTs

SAFTs became a popular way to sell tokens during the Initial Coin Offering boom a few years ago and have been used to fund billions of dollars into companies. In theory, they separate the purchase of tokens into two instruments: the first is a security to purchase tokens in the future; and the second, the tokens to be distributed at a later point in time once the protocol is live and decentralized, rendering the tokens themselves a non-security.

In reality, the court has found that the securities analysis must be evaluated at the time of the agreement and not at the time of the delivery of the tokens (token generation event). The court viewed the series of contracts and understandings relating the GRAMS tokens in their totality. They found that the larger scheme to distribute those GRAMS into a secondary public market, which would be supported by Telegram’s ongoing efforts, constituted an investment contract. Further, notwithstanding warranties and/or representations made by purchasers that there was no investment intent and that they were purchasing the tokens for own consumptive purposes, the judge looked towards the economic realities.

Adopting an Existing Token

The Securities Act of 1933 regulates the sale and offer of all securities and the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 regulates the secondary trading of public securities in the US and private securities where the company has more than $10MM in assets or 500 or more holders (including of unvested options) in any given class of securities. This may lead you to ask what happens if a gaming company adopts an existing token that is already in circulation, especially one issued by a private company that doesn’t fit the criteria for 1934 Act registration.

Adopting an existing token as a game’s in-game currency might allow you to bypass initial issuer risk (i.e., selling an unregistered security) as it was done by a third party.

“What happens if a gaming company adopts an existing token that is already in circulation.”

The flipside is relying on a third party’s network and compliance with securities laws. If there were regulatory issues with the third party’s issuance, it could detrimentally and materially impact not only the price of the token (and the corresponding economy it powers in your game), but also the existence of it in and of itself (e.g., situations where issuers have had to refund token purchasers and scrap entire networks). If this route were to be adopted, I’d suggest doing abundant diligence on such third party token, and if issued from a DAO (which would be ideal for decentralization and the reduction of securities law risk), participating in the DAO itself for some form of control and information insight. That said, as noted in the Ooki DAO matter above, you should be careful not to assume that by participating in a DAO, you are shielded from liability from decisions and omissions.

Other Regulatory Agencies

While most of the regulatory attention has been focused on securities analysis thus far, the CFTC also has jurisdiction over virtual currencies as a commodity (in addition to its derivatives jurisdiction) where it concerns fraud and market manipulation (the power of the CFTC expanded after the Dodd-Frank Act). The My Big Coin case from 2018 established that the CFTC has the power to prosecute fraud involving virtual currencies because “there is futures trading in virtual currencies.” The CFTC already regulates futures contracts for BTC and ETH. Recently, with the introduction of the Lummis-Gillibrand bill (the proposed Responsible Financial Innovation Act), we’ve seen a proposal for crypto spot markets to be formally regulated by the CFTC, further adding to the confusion and tug-of-war between the regulatory agencies over who has jurisdiction over crypto.

“As we’ve seen with the Coinbase case, you can be charged by more than one regulatory agency for the same action.”

As we’ve seen with the Coinbase case, you can be charged by more than one regulatory agency for the same action. Crypto will come under the purview of the SEC if it’s found to be a security, and any buying or selling of a security in breach of a fiduciary duty based on material nonpublic information about that security would be considered insider trading. Similarly, trading a derivative based on material non-public information in breach of a preexisting duty, or that was obtained through fraud or deception, can be considered insider trading in the CFTC context.

Wire fraud, by the way, is when one voluntarily and intentionally defrauds another out of money using interstate wire communications. All blockchain transactions conducted over the internet, an interstate wire communication, would qualify.

And last but not least, the Department of Justice (DOJ) will have jurisdiction regardless of the classification of the token or asset in question. The DOJ’s mission is to uphold the rule of law, to keep the country safe, and to protect civil rights. As they once said, “fraud is fraud is fraud, whether it occurs on the blockchain or on Wall Street.” Notably, the DOJ charged the Coinbase ex-product manager with wire fraud conspiracy and wire fraud in connection with a scheme to commit insider trading in cryptocurrency assets by using confidential Coinbase information. It also charged a former employee of OpenSea with a similar offense, adding on money laundering. Wire fraud, by the way, is when one voluntarily and intentionally defrauds another out of money using interstate wire communications. All blockchain transactions conducted over the internet, an interstate wire communication, would qualify.

“As the [US Attorney of the Southern District of New York] once said, “fraud is fraud is fraud, whether it occurs on the blockchain or on Wall Street.”

International Considerations

In early October, the European Council signed off on the Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA) regulation. After formal adoption by the Parliament, the regulation could enter force. MiCA will apply to all EU member states and will set forth a comprehensive and uniform set of regulations regarding crypto and digital assets. White papers, with detailed descriptions, will have to be submitted to the relevant financial supervisory authority. Crypto service providers, such as exchanges and custodians, will have to register in a member state if they wish to offer their products and services in the EU. If you provide these services within the game (e.g., an in-game marketplace that facilitates the trading of digital assets and currencies, and/or custodies player’s wallets), there is a chance that you’ll have to register in the EU member state if your game is available to EU residents.

Securities Summary Flow Chart

Amy is an investment partner at DIGITAL and DAO Jones, where she invests in companies building at the intersection of entertainment, fashion, gaming, and web3.

Prior to becoming an investor, Amy was General Counsel of USDC and an attorney at Coinbase. She took over the reins as lead attorney for USDC when it was at $500MM in market cap and oversaw it until around $50B. Over the past few years, she spearheaded the creation of most of the processes and protocols governing the stablecoin and network. Amy has also structured and negotiated multi-million dollar deals for the world's leading private equity firms, and worked at companies like Paramount Pictures and Major League Baseball.