Revisiting The Path to Platform

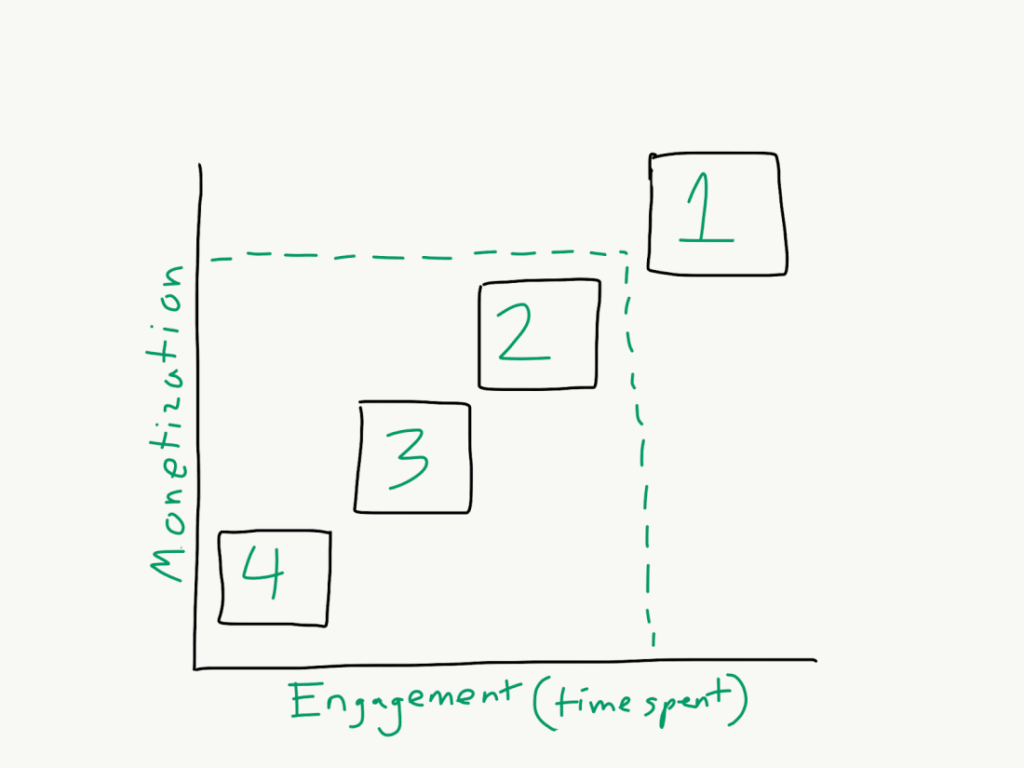

For those who didn’t read the original article, the general idea is that there are tiers of success that games and franchises can achieve. A brief summary:

Tier 4: Standalone Games. One-and-done experiences that aren’t designed for infinite play (like God of War, Uncharted, BioShock).

Tier 3: Games as a Service. Whether free or paid, these games are designed for ongoing engagement, which often leads to higher “time spent playing” and “money spent while playing.” These franchises can last decades and support efforts like esports (like World of Warcraft, Hearthstone, Free Fire).

Tier 2: Proprietary Ecosystems. These games have the ability to spark entirely new games and kickstart broader brand-driven ecosystems. Examples: League of Legends launching Teamfight Tactics in the same client, UPlay / EA Access, and Pokemon, which in a different sense, transcended into something bigger than just games.

Tier 1: Commerce Platforms. This sometimes occurs when the company behind a blockbuster game points its massive player base toward a new platform (like Steam with Counter-Strike and The Epic Games Store with Fortnite). However, paradigm shifts mean platforms can arise in other ways (App Stores, Discord, etc.).

All together, the framework (as it was) looks something like this:

As a company/game moves up a tier, it usually correlates with higher engagement and monetization. And what makes Tier 1 so special is that the company starts capturing a cut of the revenues of other businesses (as depicted by breaking outside of the green dotted line).

Any framework like this is overly simplistic and prone to exceptions. While I think what I put forward is generally correct, it doesn’t go far enough in two key dimensions.

Advertising

For one — and thanks to the subscriber who messaged me about this — it completely (and unintentionally) ignores ad-based monetization. To be fair, I don’t think advertising deserves its own tier, and the different expressions of advertising fall under the existing tiers.

- Product placement — like Monster Beverage in Death Stranding or Gatorade and Nike in NBA 2k — offers a minor revenue boost to Tier 3/4 games but doesn’t materially affect gameplay.

- Across various Tier 3 mobile games, ads are often the reason why monetization works at scale. For example, Words With Friends is free to play but murders you with ads after every move. Or Archero, which isn’t 100% reliant on ads, provides bonuses for watching ads. Ads are a big reason why Tier 3 (Games as a Service) is so mobile-heavy.

- Platforms can also reap the rewards of advertising. Companies often pay for their games to be promoted on storefronts, which adds yet another revenue stream for the commerce platforms who own the customer relationships.

I also expect (and encourage) teams to further innovate how in-game ads can work. Fortnite, for example, does a good job with brand partnerships. Also, just as internet-based display ads turned increasingly programmatic, in-game display ads (like on walls, billboards, screens, etc.) should also turn increasingly programmatic. And there’s still tons of testing to do on how gamers can “omni-purchase” — buy an item in-game that also gets delivered in real life. Is some of this crazy? Maybe. But exploring and pushing the boundaries will inevitably lead to fascinating outcomes.

Ecosystems

Second, my approach to ecosystems was lackluster. In reality, there’s a spectrum to what an ecosystem can be, and my definition was far too narrow. I think Tier 2 (Proprietary Ecosystems) remains valid — and the examples I provided are mostly fitting — but it ignores a bigger, more powerful type of ecosystem that goes beyond games, brands, and niche services. I’m talking about the titans of industry.

To better understand what I mean, take a look at traditional entertainment. Everyone these days is talking about the “streaming wars,” but that’s a misnomer. It’s really an ecosystem war (where the ecosystems aren’t really competing).

Think about it. Disney is able to offer Disney+ at a low, loss-inducing price, because the company more than makes up for those losses elsewhere in its ecosystem. Getting high volumes of people in the door with Disney+ — and, importantly, gaining data associated with owning those customer relationships — means Disney can more easily sell movie tickets, theme park passes, Baby Yoda merchandise, and so much more.

If you look across all the different streaming offerings — Netflix, Disney+/Hulu/ESPN+, HBO(Max), Prime Video, Apple TV+, etc. — it’s clear that these companies are using the same means to get to different ends. The ecosystems of Amazon, Disney, Apple, and AT&T really don’t compete… but their uniquely combined offerings of devices, services, platforms, and content ensure that there are multiple ways to acquire and retain customers, while solidifying their grips on their respective industries.

We’ll see something similar happen with video games, except these companies will often use similar means to achieve similar ends. It’s evident that the future of gaming will also include an ecosystem war, and companies — big, small, new, and old — must find ways to compete in more than one dimension if they wish to reach some form of industry dominance.

Microsoft is a good example. It owns Xbox, which will soon compete based on more dimensions than ever: powerful consoles, compelling exclusives, live operations, a cross-platform subscription service, xCloud (thanks to Azure), and streaming personalities (thanks to Mixer). Each piece reinforces the other pieces and altogether makes Xbox a tough ecosystem to compete against. Similar to Disney with Disney+, Microsoft can burn cash on something like Mixer if it means more gamers join and spend more money elsewhere in the Microsoft ecosystem.

There will always be smaller players who rock in their own ways — smart companies can find success at any tier — but fuller ecosystem wars are only going to heat up. Just look at what’s going on:

- Tencent achieves lower customer acquisition costs because it leverages its own social media platforms. They’re also partnering and acquiring liberally, building their own cloud gaming solutions, scaling esports infrastructure, and more.

- Alphabet is working to grow YouTube Gaming, kickstart Stadia, manage an enormous app store, and has committed to a few exclusive games.

- Epic Games is working to build compelling games, a competitive commerce platform, scale the Unreal game engine, and more.

- Facebook (who’s closely watched Tencent) is focusing more than ever on gaming content, is likely thinking about scaling its own games, and really wants to own the future of VR.

- Amazon sells games, owns Twitch, owns a game engine, is reportedly working on its own cloud gaming service, and who knows what else.

I could go on and on (Apple, Nvidia, Valve, Sony, Nintendo, etc.). Importantly, these colossal ecosystems don’t have to begin at Tier 4 or even with games at all. These companies can acquire or leverage what they already do to enter the industry from a unique point of strength. I also expect some of the traditional entertainment titans to get more hands-on with video games in the coming years and make games and related services part of their own ecosystems.

The industry will look radically different in a decade. Not only will mobile (and AR/VR?) be a much larger force, but technology giants are heavily investing to capture market share, and traditional entertainment titans will realize they’re losing out on one of the biggest and most exciting corners of entertainment. As industries collide, not only should we expect more consolidation (within and beyond the industry as we know it), but we should expect the dynamics of the most powerful gaming ecosystems to shift. Some traditional gaming leaders will maintain greatness; some won’t. Some new entrants will achieve greatness; some won’t. But the continued collision of hardware, software, infrastructure, content, and commerce will result in a transformed landscape.

Tweaking the Framework

It’s only fair that I add a new tier to this framework. Let’s call it Tier 0: Multi-Dimensional Titans. These are the companies that are probably already huge and compete with wide-ranging technologies, brands, platforms, and services. Due to their advantages in capital, technology, scale, customer acquisition, and beyond, I expect the best of the titans to grow even more titanic.

As a result of this new tier, I’m not sure it’s even fair to call this framework “The Path to Platform” anymore. Not all commerce platforms need to be part of broader ecosystems, and not all ecosystems need to include commerce platforms; however, the most powerful companies — the Tier 0 Titans — will own a mix of both.

Let’s call it “The Path to Titan.” The updated framework looks like this:

- Tier 4: Standalone Games

- Tier 3: Games as a Service

- Tier 2: Franchise Ecosystems

- Tier 1: Commerce Platforms

- Tier 0: Multi-Dimensional Titans

I tweaked the name of Tier 2, and Tier 0 is the new top. If I were to update the above chart for Tier 0, I’d just circle the whole thing and make it one spoke out of many (the other spokes being things like hardware, video platforms, game engines, and cloud services).

The console and PC worlds will fall into Tier 0 ecosystems first. Mobile, with its more distributed array of studios and publishers, is a bit more immune, but I suspect the biggest players — especially as more live, multiplayer action games with big brands drive mobile growth — will slowly start to fold in.

Whatever the case, all this change and possibility means it’s an exciting time for the gaming industry, and there’s no shortage of opportunity to build things that make a difference. That said, it’s important to ask how what you’re playing, building, or investing in will adapt to a world where industry titans with multi-dimensional ecosystems gain ground. How are you positioned?