Hi everyone. We’re excited to see you at GDC 2023! In partnership with Leanplum, we’ll be co-hosting a VIP party on March 23rd from 8:00pm - 9:30pm in San Francisco. Longtime Naavik contributor, Fawzi Itani, will be there to represent our team, apart from more Naavik folks, and we’d love to link up with you at the event.

RSVPs are limited to 200, so please be sure to hit the button below and RSVP soon. Apart from a ton of networking and knowledge sharing, we’re also looking to discuss how Leanplum + Clevertap are thinking about evolving the future of player personalization systems in games, which we believe is going to become an increasingly important strategy in a privacy-first product and marketing world. See you there!

India x Web3 Gaming & Next Up With N3TWORK

Manish Agarwal: India x Web3 Gaming In this episode, Manish Agarwal – ex-CEO of Nazara Technologies and founder of IndiGG, a web3 gaming DAO focused on India – joins Naavik co-founder Aaron Bush to discuss what guilds initially got wrong. Manish dives into why he prefers to not use the term “guild,” and how India might become a digital asset factory. The duo also discuss the size of the web3 gaming opportunity in India, and why India could be a uniquely effective market for web3 gaming, as well as learnings from working in a DAO - the underappreciated benefits and the ongoing challenges. Manish also shares what IndiGG’s strategy is going forward, plus his views on what he looks for in partnerships and games Website | YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcast | Google Podcast.

Next Up With N3TWORK (Mobile Pivots to Web3) Founded in 2012, N3TWORK Inc made its mobile gaming debut with Legendary Game of Heroes, a hit match-3 mobile RPG. Today, N3TWORK Inc has fundamentally changed its tune and is pivoting the business from web2 to web3. Today, your host Alexandra Takei, sits down with Matt Ricchetti, President of N3TWORK Studios, a spin out from the merger of N3TWORK Inc with Forte. Backed by Griffin Gaming Partners and talent from legendary juggernauts like Zynga, Glu, and Kabam, what is N3TWORK’s strategy, what are they building, and what’s their perspective on the web3 in the bear? Website | YouTube | Spotify | Apple Podcast | Google Podcast.

Are Gaming VCs Too Big?

The game industry has seen an unprecedented surge in early-stage venture activity over the past two years. I’m not sure I can name another industry for which 2021 & 2022 private investments separately make up 5%+ of the total market like it has been for the gaming market, according to numbers from Newzoo’s report (perhaps gaming is still just too… small?).

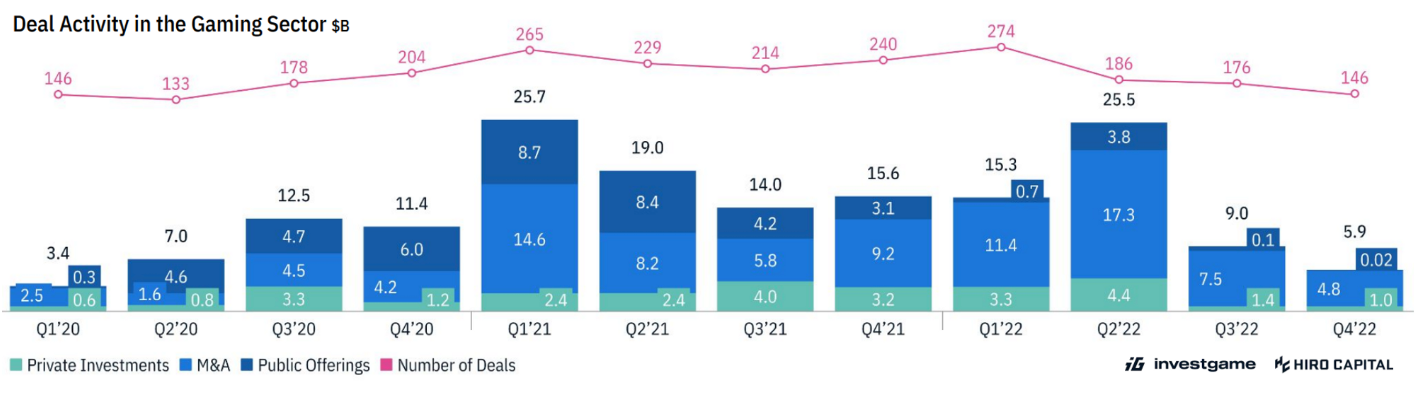

According to Invest Game’s quarterly report, 2021 private deal activity ballooned to $12 billion across 562 deals — almost double what it was in 2020 — with 2022 private deal activity slightly dipping to $10.1 billion across 538 deals. As they show in their report, deal activity has also started to decrease these past two quarters, indicating a normalization of private investments in the space (or at the very least some more judiciousness when it comes to valuation).

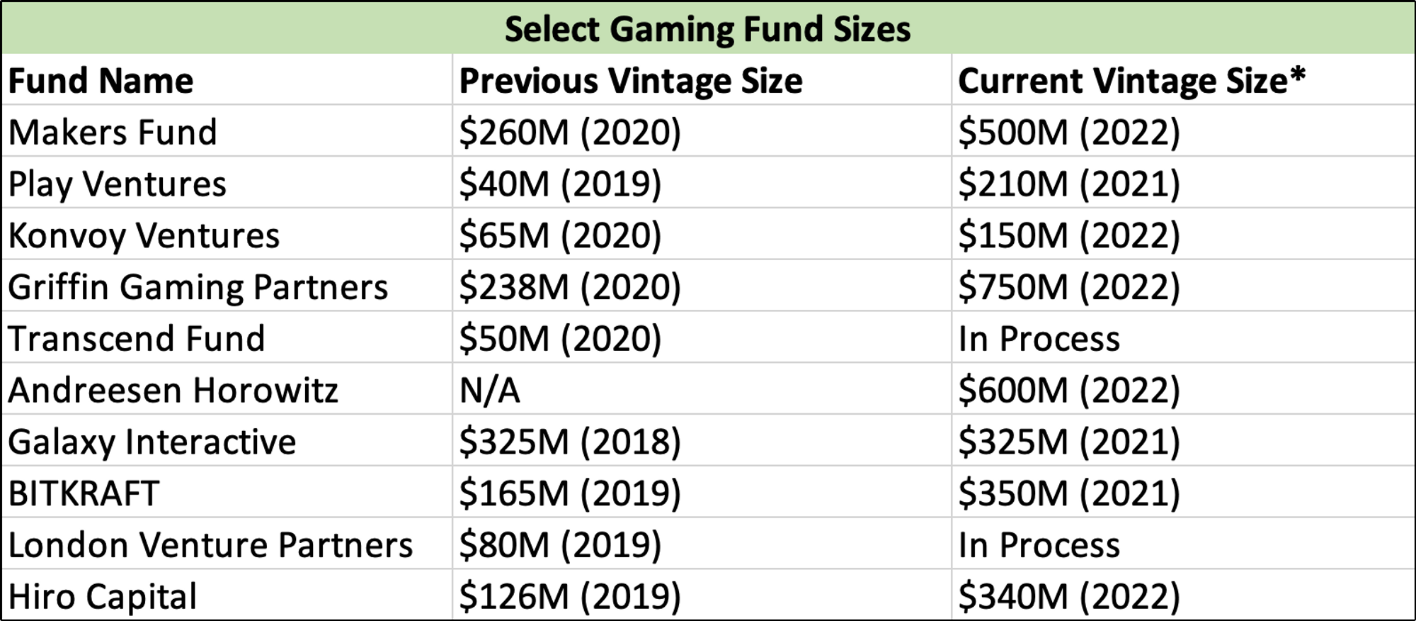

To meet this growing supply of video game startups in the space and burgeoning institutional interest as a venture-backable category, venture capital firms have raised ever-larger larger funds to deploy. Venture has driven outsized returns to LPs over the past 10 years, why should gaming be any different? Over the past few months, it’s been interesting to have conversations with friends and investors on the state of gaming VC — one topic that has continued to come up: are fund sizes too big? In other words, given the historic returns of the category, competitiveness of the space, deal sizes, and fund goals, should these gaming vintages be smaller?

The goal of this article is to explore the size of gaming venture funds in the context of venture exits in the space — can they justify their fund size? It's also to provide some perspective on the VC point of view and the goals of many of these gaming funds so that entrepreneurs can be better equipped to navigate their own fundraising. But first, it might be helpful to ground ourselves in some basics regarding gaming VCs (and VC more generally):

- For a VC, the goal is not only to “return the fund,” which means to return all capital plus management fees (typically about 2% each year) to a fund’s LP base by the end of a fund lifecycle, but also to return more. In fact, much, much more. Fund performance can be viewed in a variety of ways (for example, did it outperform alternative areas where someone could invest like the S&P?), but one of the most common is in relation to other VCs in the same sector — that is, relative to other VCs in the gaming industry in the same vintage, how did X or Y or Z fund perform?

- To drive outsized returns, VCs have a target amount of ownership in a company. With each funding round, existing shareholders typically are diluted with the addition of new capital by other VCs. However, some agreements have pro-rata rights, which allows for existing shareholders to maintain (or increase) their ownership by investing the requisite amount of capital.

- Why do gaming VCs exist? It’s a really great question to consider when some of the best outcomes have included other marquee generalist VCs like Index (Supercell), Benchmark (Riot Games), Thrive (Unity), First Round (Roblox), LSVP, and so many others. While gaming is inherently a “consumer” or “platform / infrastructure” category, it also requires having in-depth knowledge around development cycles, entrenched networks for recruiting, patience for content production, an eye toward play testing, use of funds (for example when to launch UA), and marketing. In short, games investing is nuanced enough to warrant its own specific funds.

As we can see from the chart above, the size of gaming VC funds has doubled (or tripled in some cases), with the notable exception of Galaxy Interactive. Let’s ground the above points in an example. While it’s always tough to determine fund performance, Play Ventures had a $40 million first vintage in which it exited Reworks for around $600 million at Series A. It’s not unreasonable to think that after leading the seed, Play Ventures owned somewhere between 10% and 15% of the company, allowing it to return the fund off of this one investment (speaking of which, looking from the outside in, Play’s first fund is awesome).

If we were to extrapolate this out to their second fund of $135 million (separate from their $75 million crypto fund), the hypothetical exit of Reworks would not have returned the fund at the same ownership level. The dynamics of ownership, funding, and return profiles completely change with a larger fund. On the flipside, with more capital comes a greater ability to secure more ownership in a company allowing Play to pursue different types of companies at different deal sizes. At 10-15% ownership at the seed, a hypothetical exit scenario would require Play to return a $1B+ outcome.

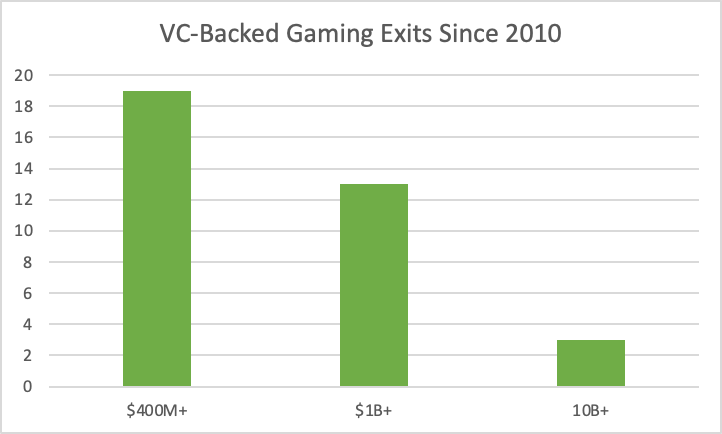

However, the stark truth of the gaming industry is that there have been very few large exits. There have been 19 VC-backed video game companies that have exited above $400M in the past 10 years (of which 16 exited for $1B+). 15 of these deals were content deals and four were platform / infrastructure (Roblox and Unity, for example, make up two of the three $10B+ exits). There are a few notable exits like AppLovin or Mojang that didn’t raise early stage VC (or very little of it) that aren’t represented in the chart. Notably, a large portion of these companies were not funded by games-specific VCs given they were funded in early 2010s and a bulk of gaming VCs were founded in the past 3-5 years.

How do we reconcile these numbers with the amount of gaming VC firms with large funds today? For one, there’s certainly an analysis to be done about gaming companies that are VC-backed and valued above $400M, of which there are many: thatgamecompany, Theorycraft, Rec Room, Niantic, Homa Games, Overwolf, Dream, and Triple Dot are all examples of companies that fit this bill but the data is too incomplete and inconsistent to conduct a full analysis (we’re working on it in our new Naavik Pro financial markets vertical, stay tuned!). There’s also probably an analysis to be done on the dynamics of 2021-2022 investing in games to understand how valuations might shift with time.

Much like other sectors in the VC space, company valuations skyrocketed following a pandemic-high, and there might be a reckoning coming for all sectors — valuations decreasing, recapitalizations, companies shutting down after being unable to raise. My gut also tells me part of the reason gaming VCs raised more capital (aside from this being the natural progression of successful funds, of course!) is that the space is small, deals are circulated quickly, and having the capital to compete with others in the space on valuation while maintaining ownership was incredibly important in the 2021-2022 period. Raising biggers funds was important in order not to be outcompeted from a deal process, particularly for smaller funds.

Late last year during an industry-wide slowdown in VC funding, my colleague Miikka wrote about alternative sources of funding for video games. It’s true that not every company will need (or meet the characteristics for) venture funding, but I remain excited about the potential of venture funding in games for a few reasons:

- Talent Density: There are more games entrepreneurs than ever before starting their own companies. Some have left reputable companies like Riot Games or thatgamecompany. Others are starting their journey from different paths like web3. And some are looking for new opportunities after being laid off. Whichever approach, the level of talent out there is insane!

- M&A Activity: While there might not be as many record-breaking acquisition announcements as January 2022 (Activision, Zynga, and Bungie), the amount of M&A activity over the past two years has been unprecedented in the games space. The FTC certainly seems to be more scrutinizing these days; while it might slow acquisition activity, this shouldn’t stop the interest by larger gaming and tech in games. More importantly, M&A activity & potential gives space for VCs to be optimistic about exit opportunity in their own companies.

- Business Model Changes: From subscription to cloud gaming to geography expansion, companies are looking inward into how they can level up their own organizations. Business model change always creates new opportunity for new entrants to move faster than incumbents — which companies will skate to where the puck is heading and deliver superior player experiences and outsized returns?

It’s important to take a step back every once in a while with a critical eye. Gaming VC funds sizes (and the number of gaming VCs out there) are undeniably large given historic venture returns in the category, but I’m also optimistic about the opportunity ahead. Perhaps because of the reasons above, the next decade will yield even bigger companies than the decade prior. Maybe these funds will even grow larger than they are today. (Written by Fawzi Itani)

Content Worth Consuming

The New Gold Rush (GameCraft): “Mitch and Blake take on the complex topic of in-game economies. They discuss how the endemic problems of trust and arbitrage were present in the earliest in-game economies of the late 1980 and how they have persisted to the present web3 economies. They look at the concept of mudlfation, a unique economic problem of massively multiplayer online games, and the strategies for controlling it, as well as the idea of economic play.” Link

Lessons From 25+ Years Of Games Leadership (Game of Life): “Jonathan Knight is the Head of Games at the New York Times. He's had a multi-decades long career in games, and we dig through his learnings from working on games like Sims 2, Harry Potter: Wizards Unite and Words with Friends, and working with people like Mitch Lasky and Will Wright. We also talk about the interesting opportunity for games at The New York Times, the global sensation that is Wordle, and Jonathan's outlook on the future of games.” Link

Mobile Gaming Report 2023 (YouGov): “Mobile gamers must not be viewed as a monolith, however. From hardcore adventure gamers to the casual puzzler, the mobile gaming market is incredibly diverse, and the products they’re likely to buy next vary as well. This report, drawing on December 2022 data from YouGov Profiles, provides advertisers an overview of the market before providing snapshots of players of various mobile game genres and intent data on what products they are in market for in 2023.” Link

On Building LoL and Arcane (Good Time Show): “League of Legends is not just a game but truly a *phenomenon* - creating an entire category of gaming, events, perhaps esports itself and now a hit TV show on Netflix. We had the pleasure of getting to know Marc Merrill over the last year and when we got him to come on our show, we knew this would be a special chat. Marc is president and co-founder of Riot Games, the creator of League of Legends and especially around hit TV series Arcane (if you haven’t seen it, highly recommend it whether you’re a gamer or not). This was a blast from start to finish.” Link

🔥Featured Jobs

- Modulate: Content Marketing Associate (Somerville, Massachusetts)

- Carry1st: Head of Product Marketing (Barcelona, Spain | Remote)

- Merit Circle: Head of Investment & Partnerships (Amsterdam | Remote)

- FunPlus: Lead Game Designer - New Casual Studio (Barcelona, Spain)

- Flick Games: Chief of Staff (Remote)

You can view our entire job board — all of the open roles, as well as the ability to post new roles — below. We've made the job board free for a limited period, so as to help the industry during a harsh period of layoffs. Every job post garners ~50K impressions over the 45-day newsletter featuring period and results in 1 - 10 applications depending on the company and role.